The sad but true reality of professional Psychology in Italy: the most hated job is also the most profitable

February 20, 2021

The truth students should learn before enrolling in a Psychology Degree.

For a while I have been pointing out at some elephants in the room of professional Psychology in Italy.

For those who missed on my continuous rants, here is a short breakdown:

1) There is a critical overabundance of psychologists. In 2018 (3 years ago), there were a staggering 109.524 certified psychologists on the Italian peninsula, with the number of non certified practitioners way higher.

2) The market demand cannot provide a sufficient income to sustain all these professionals. On average, 1 in 2 psychologists earn somewhere around 9.000€ per year, which is around 750€ per month. More worryingly, 1 in 10 psychologists earn less than 500€ per year. Overall, it is safe to say that the majority of psychologists earn less than a minimum-wage pay would grant then.

3) Most devilishly, certified Psychologists often earn by certifying other psychologists, generating a downward spiral in the profession. To expalin:

A psychology student in Italy must possess a minimum of 5 year of university studies, and must work for another certified psychologist (often for free) for a whole year in training before passing a final abilitating exam and be considered a psychologist.

On top of that, to become a psychotherapist, psychologists must often spend additional 2–5 years in training from another trained psychotherapist (see a trend here?).

All these certifications (often not enough to be competitive on the market when considering that the majority of psychologists have them) are quite expensive and require constant and dedicated effort of our young workforce.

This results in a proliferation of expensive schools, masters, seminars and webinars of dubious utility, that further delay the training of the psychologists, and further drain their short finances.

To add insult to injury, there is a small but emergent area in psychology which seems to have better luck: marketing and communication psychology.

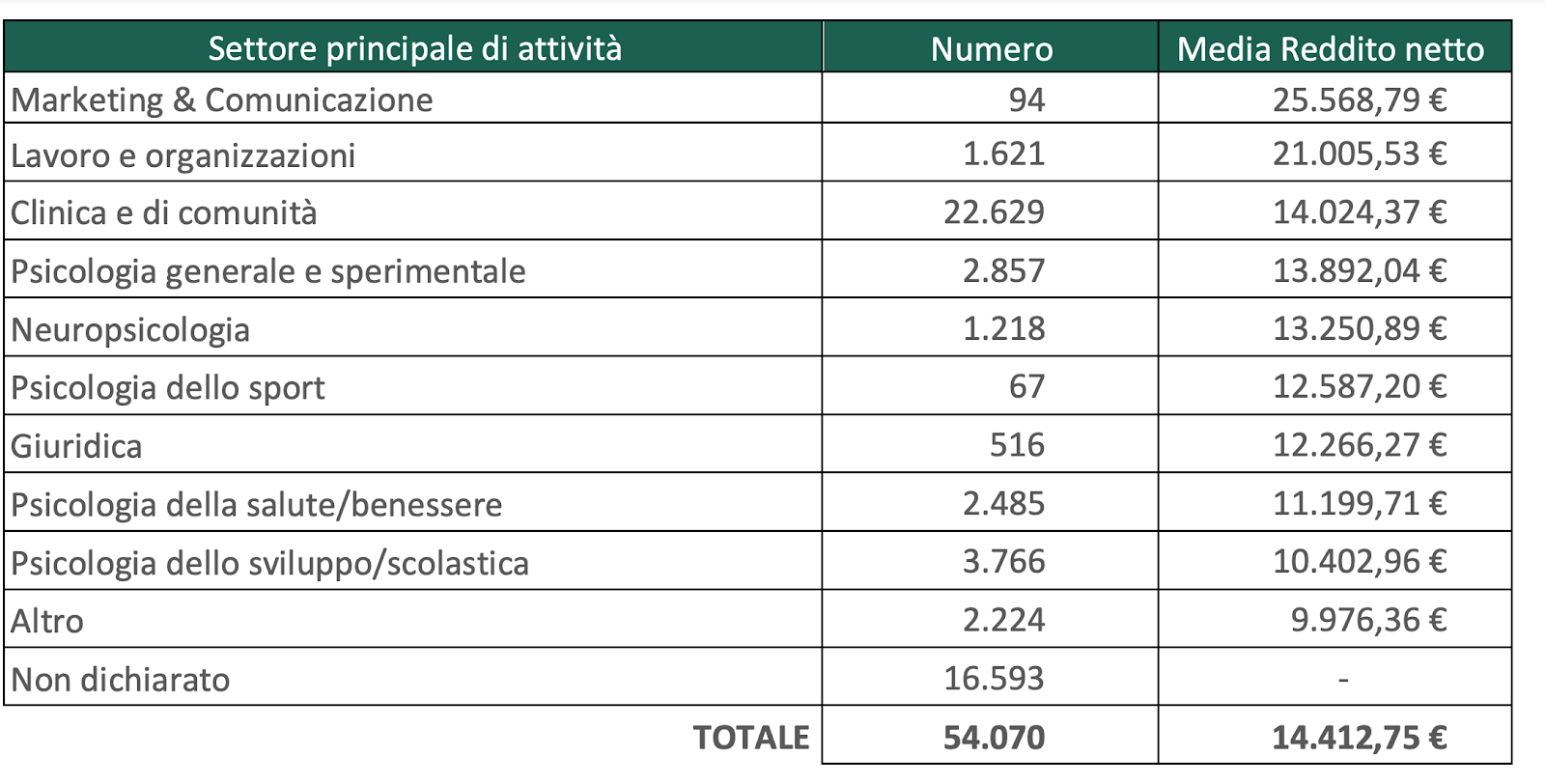

An ENPAP report of 2018 shows how psychologists who work in marketing and communication grossed the highest in the profession, as much as 1.8 times more money on average than clinical psychologists. The number goes even higher when comparing the average revenue of marketing psychology to the one of school psychologists, the former grossing two times and a half more money on average than the latter.

Here comes the funny part: only the 0.002% of psychologists are marketing and communication psychologists. Yea, you read well, that number is correct.

The truth is that a dominating majority of psychologists loath marketing psychology, considering it a profession of tricksters who use the knowledge obtained from psychology courses to fool people into buying stuff they don’t really need. As a consequence, most young students steer away from manuals in communication, perception and social psychology. I still remember the “Ehw, why would you do that?” reaction that I got when telling other colleagues of my decision to work in the field of marketing and applied psychology.

This is a pity, not only considering that there is a huge need for trained and effective marketing psychologists in the market, (that 0.002% means that there is space for way more professionals in the field), but also that most marketing psychologists I know could not be further from the “evil trickester” stereotype.

Take, for example, Chiara Bacilieri, a young marketing psychologist and manager who, among many other things, works at Lifeed, a company promoting workers’ well being using psychology and Big Data.

My hope is for the next generation of young Italians to see the numbers above before making their decision of going into psychology.

More than that, I wish to remind all psychologists, young and old, that psychology is a flexible discipline which can find applications in the most disparate of fields. In fact, I believe that professionals who “stick their head out” and apply psychology to new and emerging fields will be the ones that will innovate (and profit) the most in the field.

In the end, professional psychology need not to become an elite, but could be more aware of its limitations, especially when making promises to young students.

Sources: 2018 ENPAP report